Morning fog hangs thick and soupy over Bodega Bay where I have landed for a few days. Every ten seconds or so, a foghorn sounds in the distance, a melodic heartbeat, punctuated now and again by the throaty croak of an elephant seal pup. Seagulls salt the dark gray sky. And goldfinches––males bright yellow of breast this time of year––bounce from thistle to vine, then dive into dense, marshy brush. This is how we live here, they seem to intimate, with levity, color waking gray, and song.

Traveling north on Sunday, I slipped onto Highway 1 shortly after crossing the Golden Gate Bridge. The early morning, dripping with mist from a low-hanging fog, lent a certain silence even amongst the tourists filing out of buses one by one at the Vista Point overlook. I had stopped there for the night to wake with the Bridge and Bay in view. While not the most peaceful night’s sleep, it did reward when I woke with an otherworldly aura given by the mist. Only two-thirds of the iconic uprights were visible, the uppermost third but a suggestion. The eyes of a child in me saw a giant ladder ascending into heaven and another in the distance, heaven there one rung closer. . . .

Connie, my host in Oakland, long-time mentor, and friend, had asked where I would go next, suggesting that in my quest for places wild and holy, I might consider a stay at New Camaldoli Hermitage in Big Sur. Though I had fancied myself heading north next, I liked the idea. But I learned that a mudslide just days before on Highway 1 near the Hermitage had foreclosed access for several months. Connie had another idea much closer to home: the Buddha of Oakland. We planned to make an afternoon pilgrimage the next day. Little did she say in advance about this sacred site but that we must go.

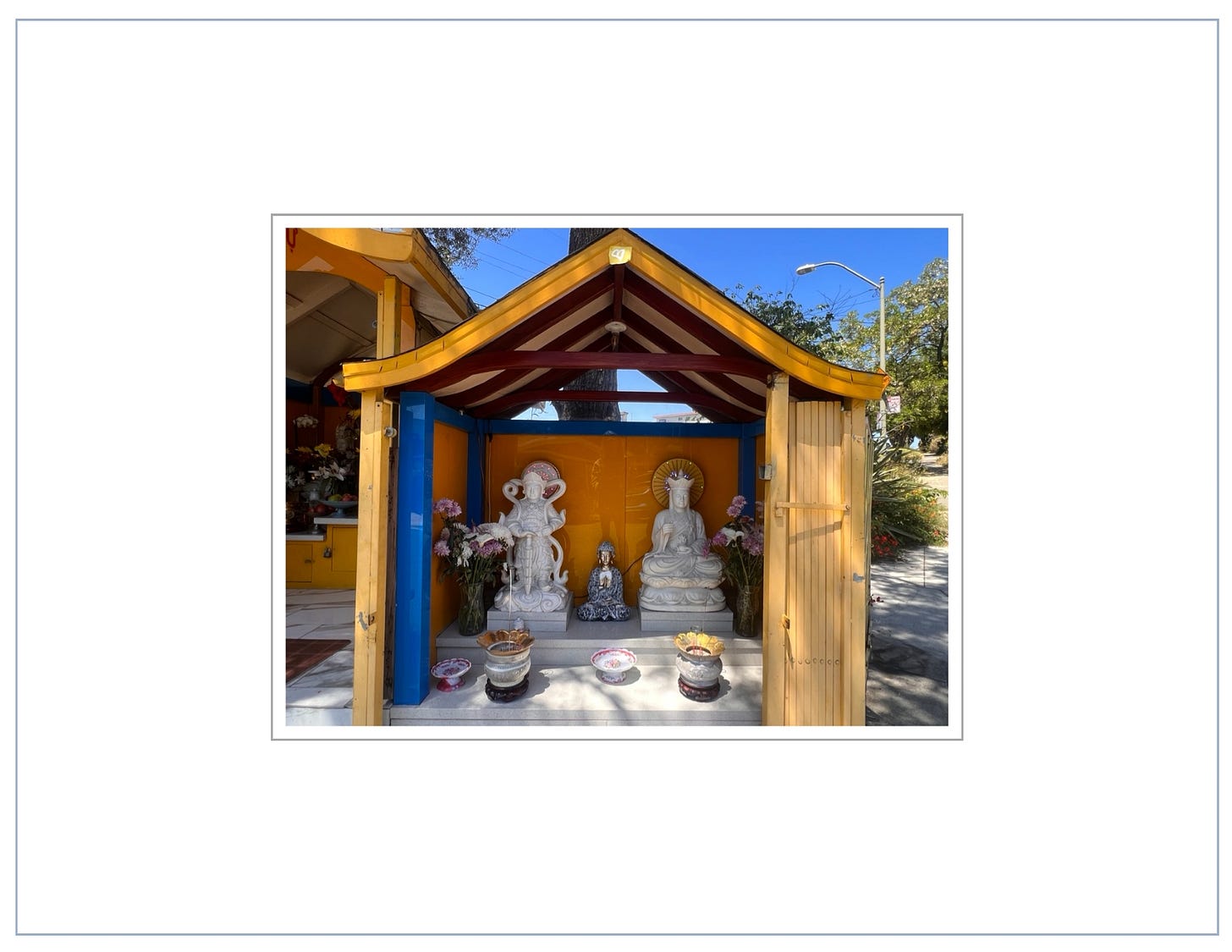

Our path seemed circuitous. I could not find my way back today if you gave me a paper map with a gold star marked “Destination” and drew red lines to direct me down the roads I should take. We wove around city streets wide and narrow, up and down hills, skirted alongside Lake Merritt, and ventured into the Eastlake neighborhood, finally slowing pace near the juncture of 11th and 19th. On the corner stood four shrines adorned with offerings of nurturance––mandarins, apples, pears . . . and candy––and fresh cut tulips, gladioli, and lilies, amongst pots of orchids in vibrant bloom, all to glorify the Enlightened One. Countless sticks of incense, having burned to nothing but the red base that held them upright, whispered worship. A plaque read Pháp Duyên Tự, which, roughly translated from Vietnamese, means Dharma Temple.

I was drawn immediately to Quan Yin. It was a felt sense of being called to her, something inside me shifting, getting quieter. Behind her head, a halo blinked of rainbow-colored lights, not unlike those that twinkle on Christmas trees. There were deities I did not know and a golden Buddha assuming the Abhaya Mudra of blessing (or protection). In the center sat the One affectionally named The Buddha of Oakland, wrapped in a gold robe, a halo twinkling rainbows of color behind his head, too. His eyes were closed, his belly soft––to receive the breath and let it go, no effort. He was seated on a throne high above the other beloved ones, marble at their feet, hand-carved wood forming the beams overhead and marking the openings to three golden-colored shrines and a fourth white shrine erected one by one over a span of years. The entire sanctum rose from a traffic barrier that was constructed in 2008 to slow speeding cars. It was set back just barely from the curb.

From a certain way of looking at things—meaning, given the curbside context—one could say when approaching this shrine, “What’s so holy about this place?”

But that way of looking would be to fail to see.

The Buddha of Oakland is a concrete buddha, a statue purchased from Home Depot by a man named Dan Stevenson. I met Dan on the day that Connie and I made our pilgrimage. But it was Lu Stevenson whom I met first. By the time Dan came to the conversation, Lu had already volunteered answers to a cadre of questions that had surfaced while I stood before the shrine, and she filled in gaps to myriad more questions I did not think to ask. Dan seemed to shrug off the role he played in seeding this sacred site, not because he believed any of it insignificant. Rather, I picked up on a blithe modesty about it all.

Drug-related crime and prostitution in the neighborhood followed the construction of the traffic barrier in 2008. Dan comments in this podcast that it was the heaps of trash that finally pushed Lu and him to the edge.1 The barrier had become a dump––broken furniture, used mattresses, piles of discarded household goods, you name it.

Lu told me the thought came to her one day to place a buddha statue over there. Dan liked the idea. A buddha would be a neutral religious symbol. It was a long shot, but the statue just might inspire a little respect.

Dan shuttled over to Home Depot and bought a concrete buddha. But it sat in their basement for months because he was sure it would be stolen if he put it out there without affixing it to something. Finally, he fashioned a way to fasten it to a stone with rebar and epoxy and placed it in the center of the traffic barrier where it sat, tucked into unkept flora, untouched for months.

One day he noticed the concrete had been painted white. Someone had taken notice. This was in 2009.

In 2010, a group of local Vietnamese residents came to clean the statue, repaint it, and leave offerings. In time, they built a wooden shrine around it, and another and another, adding deities and Quan Yin. By 2012, the shrine had become a meeting place for daily worship. This remains true today.

By 2019, overall crime in the area had declined by 83%. Robberies had dropped by 90%; burglaries by 50%. And narcotics, prostitution, and dumping of trash were non-existent.2

Why?

What makes a place holy? What makes a place empty us into silence? Steal our breath in awe? Stir us into wonder? What makes a place linger inside? Leave imprints on our psyche? (Or is it soul?) Leave us changed for having been there?

If I walk into a temple or chapel or shrine, a desert or forest or meadow, and cannot see nor hear but am stilled nonetheless by what I feel in the space around and within me, what was it that stirred me?

Surely, there are those before me who have asked what evokes a sense of the sacred in a place and written about it. (There are.) Surely, I could read what others think about such things. (I have but not nearly all.) Even so, reading what others have to say is not my inclination here. I prefer to come to these questions phenomenologically and in dialogue with you.

Phenomenology is a philosophical method of inquiring through lived experience into the phenomenon one experiences. We let that something live in us until we and the something are in a suspended dialogue––the phenomenon evoking and by its evocation invoking something within, bringing us to a knowing we didn’t know before––or didn’t know we knew because we now know it differently. Ever so strangely, we must unknow to let what is reveal itself to us as is and not as we think it is.

For a place or thing to be rendered and experienced as holy, it must be allowed to reveal itself as intrinsically whole, whether the place or thing is a seaside, a statue, or a street corner. Life happens in places and with things.

I keep coming back to Lu and Dan’s initial impulse and the community of people who came to the statue, cleaned it, painted it, made offerings, and worshipped. Lu and Dan were moved by an inner recognition of the sanctity of a symbol. This recognition, I later learned from Connie, a sociologist of religion, is birthed of the phenomenon of popular piety. Popular piety is the “spontaneous devotion prompted by the recognition of a religious icon.”3 In other words, the concrete buddha serves as a totem of the Buddha. The symbol lends an as if that sparks devotion. What I gathered from Lu is that the idea to place a buddha where the trash was being dumped came to her as an invitation to invoke piety of place. And the community who took notice and came in presence and by their labors and offerings and worship imbued a sacredness that can only come with devotion onto what was once but a manufactured concrete statue. And what is devotion if not care that comes forth from affection?4

Devotion. Care. Affection. These are outward expressions of inward feeling. What is the inward feeling from which they arise? And what is the inner orientation that avails us to this inward feeling giving rise to the expression toward a thing, a symbol, a place, an Other?

Humans desecrate. Humans consecrate.

We come now to what may be hard to stomach. But we come at the same time to promise.

The corner of 11th and 19th was once a desecrated place. The things tossed and shoved aside there were desecrated things, things cast off as useless, robbed of any care. And the place where they were tossed became itself a desecration.

Human lives become desecrated, too, when we are cast aside as insignificant, unworthy, meaningless, as bodies to be used. When we believe our lives to be desecrated, we become lives that harm other bodies and bodies our own just to survive the madness of being alive in a world experienced as wholly absent of care.

Humans trash desecrated things and abandon what we perceive to be desecrated places . . . and lives. We do so blind to our participation in making desecration so. But the story of the Buddha of Oakland lends significance to the simple, albeit profound, act of care, care that comes out of affection. This, we call devotion.

Of the Buddha of Oakland, could we say that devotion to the symbol gives significance to the place where it sits? For some, that symbol may appear to be nothing more than a manufactured mold of concrete in the shape of a sitting buddha purchased from a big-box, home-improvement store. How many thousands of them are there? Yet this one––and perhaps countless others given the same devotional care––has been consecrated, has been made holy. I am searching here inside popular piety as a contagion, recognizing that there are those who do not register the symbol as sacred but are touched nonetheless by the care for it by those who do.

Does care create an aura around it? If so, might popular piety point a way toward care for the materiality of our existence? Might living with care make of the things and places and lives we touch more holy? What if we turn that question around, flip it on its head? Might living as if all is holy make of the things and places and lives we touch more worthy of our care?

Spiritual traditions tell us to let go of our attachment to the materiality of the physical world and to our bodies. To do so is to transcend maya, illusion, our attachment to stuff, and to live with our end ever in sight because in the end, there is no body, no stuff. I would not suppose to contest the wisdom of the ancient traditions the world over. But I cannot help but wonder with the late visionary, Thomas Berry, if we have veered too far in our faith in transcendence and as a result, wreaked havoc on the planet and all life, including our own, by our lack of care.5 We see in the Buddha of Oakland the power of care for what ostensibly could be called a thing made no longer merely a thing but a sacred embodiment.

Care beholds this thing, this place, this life as a sacred whole. And because this is so, we, of our care, are consecrating beings.

Could we say then that holy is a way of being? A way we meet the world in all its materiality? (L. materia from L. mater for matter. But before mater meant matter, it meant mother.)

What would be that way?

Might we venture that holy is not so much how something appears to or is experienced by us as how we come to it––with and of our care, our affection, and devotion?

These are but a few of the questions lingering in me from this inquiry on wild and holy that emerged as a theme for the month of May, an inquiry never complete. But it seems time to move on and let the questions be lived now and reflected upon in our own time and in comments for those so inclined. Since I am setting off to wander wine country in the days and weeks ahead, which invariably tends toward good food, I am inclined to play in the Dionysian playground of pleasure to the senses as a theme for June. We shall see. . . .

As always, I am ever grateful you are here.

Here I am with Connie’s dear friend, Suki, for whom my affection is unmatched!

Dan Stevenson and Phoebe Judge, “Episode 119: He’s Still Neutral,” Criminal Podcast, Criminal Productions, July 19, 2019. https://thisiscriminal.com/episode-119-hes-still-neutral-7-19-2019/

Constance Jones (2019) “Popular Piety: The Buddha of Oakland, California,” Paper presented at CESNUR (Centro Studi sulle Nuove Religioni, "Center for Studies on New Religions") Turin, Italy, September 2019.

Ibid.

I borrow from Connie here about the profundity of affection. Constance Jones, personal conversation, May 27, 2023.

Thomas Berry, Evening Thoughts: Reflecting on Earth as Sacred Community, ed. Mary Evelyn Tucker, (San Francisco: Sierra Books, 2006).

See also Renée Eli, “Body, Being and the Emerging Ecozoic: Thomas Berry’s Relevance to Modern Medicine, The Ecozoic: Reflections on Life in an Ecological-Cultural Age 4 (2017), FN 5, p. 172.

Thank you for sharing, @Martino Dibeltulo Concu !

Renee; As I said, you are increasingly becoming more poetic as you explore life around you, and I love reading your entries even more. You could say that poetry is the only true way to view and describe this magical planet we live on. I love this question you posed: "Might living as if all is holy make of the things and places and lives we touch more worthy of our care?" All is truly holy depending on how you view it and are moved by it. Even the desecration I might add, though that is a hard one to wrap my head around. It's all part of the whole; all of life and all the behaviors of humans, even the misguided ones that lead to desecration and harm to others and the planet. If I can reside in that belief, then nothing is not holy, for all is from the Source, even our ignorance. It's that sense that joy and suffering are inseparable here in our existence, and surrendering to that truth leads to acceptance of all of it, even the desecration which stems from our inescapable wounding as these vulnerable human creatures. From there compassion can flow for everyone, and I'd say, even more so for those deeply wounded beings who out of their wounds desecrate life around them. As always, here's a poem for this day; about turning to the natural world when one is lost in fear, to remember that all is holy: "When despair for the world grows in me, and I wake in the night at the least sound, in fear of what my life and my children's lives may be; I go and lie down where the wood drake rests in his beauty on the water and the great heron feeds. I come into the peace of wild things, who do not tax their lives with forethought of grief. I come into the presence of still water, and feel above me the day blind stars waiting with their light. For a time, I rest in the grace of the world, and I'm free."

...Wendell Berry.